chris carroll

We were a week overdue, and beginning to wonder if we'd ever have this baby. Liz was getting darn sick of sleeping with three strategically placed pillows to support her distended body, sick of not being able to bend over or lift anything. All through pregnancy Liz had been getting Braxton Hicks (or was it Bachman Turner?) contractions, which are basically practice for the real thing. Just in the last few days though, they had changed. Liz had said several times on Thursday, "Something's going on down there", so we hung around home, had a normal dinner. While sitting at the table, Liz yelped out loud at the pain and surprise of a contraction, and we both knew something was definitely up.

I'd say labor started around 7 pm. Liz's mom had told us about how she went into labor with Liz: ate Chinese food, went to bed, woke up, went to the hospital, had her baby. Bap, bap, bap. No sweat, no strain. We had talked a bunch (and listened in class, read books, etc) and had discussed how difficult it was to be, but I still think some wishful thinking was going on at this point. Trying to follow Doe Mechem's model, we went to bed about 10. The contractions kept up, and kept Liz up, fairly steadily. I, of course, fell right asleep. At midnight a particularly poignant moan woke me. OK, says I, this is it, no more monkeying around. I got on the horn to Patricia and the doctor, and got up and began making tea, turning on lights, seeing what I could do to make Liz comfy.

One of the main things emphasized by our doctor, our birth class, and numerous books and friends, was not to go to the hospital too early. I figured we'd be home most of the night, and head up to Beth Israel around daybreak, if not later. 'Twas not to be the case. It was clear to me early on that the contractions were far more intense than Liz had figured on: jarring, searing pains that made her cry out in pain. I'd been steeling myself ever since fainting at the amnio for watching her be so miserable and it didn't throw me as much as it did her. We spoke to the doctor again around 1 or 1:30 and she said she'd get up and head over to the hospital and meet us whenever we were ready. Liz was convinced she was cruising through the stages of labor with extraordinary speed, and I have to admit I didn't put up a very forceful argument. I just knew we should be hanging out in the house for longer, but I couldn't argue with my lovely, pained wife. Our friend Patricia, acting as coach, arrived breathlessly minutes after my phone call. Surprisingly, she seemed immediately ready to go to the hospital. I had expected her to help me try and keep us home as long as possible. Another thing is that one of my biggest (and silliest, I know) fears all along had been being forced to try and hail a cab at rush-hour, so leaving in the middle of the night appealed to me from a transportation standpoint as well.

Back on the ranch, Patricia and I had been timing contractions for an hour and a half or so, and they were all over the map, but in a generally shortening length. The rule of thumb is go to the hospital when you have contractions every four minutes, for a full minute, and this pattern extends for an hour. We definitely weren't there, but some of the contractions were every three minutes, and some over a minute and a half.

This whole period, in contrast to Patricia and I, Liz had been worrying more about Otis than herself. I know the big guy can handle himself, but since Martha was out of town on business, and Ondine wasn't answering her pages, it seemed the Fur might have to spend some time alone. I was a little worried that he'd be freaked by all the obvious commotion and stress, followed by his three favorite humans leaving the house in the middle of the night, but I know Otis is a generally low maintenance dog. Even missing a dose of his drugs isn't that big a deal. I think maybe Liz was transferring some of her fear and worry for herself to Otis, or maybe she just thinks he's more fragile than I do. Whichever, I remember as many discussions over how Otis was doing as how Liz was doing. Within a half hour of the doctor’s last call, it became clear Liz wanted to leave for the hospital. Patricia gave Otis a last walk, then went downstairs to hail a cab. Liz and I waited for a good long contraction (and its correspondingly long quiet period), and then headed downstairs. Even with all the activity, stress, and confusion, Otis actually didn't seem that fazed, and accepted our departure with nary a whimper.

I locked up the apartment and came around the bend in the stairs to find Liz doubled over in pain. The contractions were coming hot and heavy, maybe it was indeed time to hit the hospital. Patricia had the cab waiting with trunk and doors open, so we threw the bags and ourselves in and proceeded. We asked the driver to drive carefully, and told him why, and he chanted in a thick Haitian accent, "I don't want no baby in my cab", but did indeed drive gently up to 16th and first. Liz was in and out of lucidity at this point, but she came out of her stupor to exclaim, “Crosby street! He’s taking Crosby, it’s the only one with cobblestones and the worst pavement in New York!” Yeah, but only for two blocks. We managed to get through Crosby, and all the way to Beth Israel. Right as the cab pulled to a stop, a really severe contraction hit, and Liz was doubled over gripping my arms bearing down through it. I thought the cabbie was going to burst an artery, convinced that we were going to ruin his cab. I tipped him an extra ten.

The tour of the hospital we'd taken several weeks earlier came in handy as we easily navigated our way to the delivery ward. When you arrive, the mother-to-be is taken into triage. Because there are three beds in there, no husbands or helpers are allowed. Patricia and I dutifully trooped into the little room with the blaring rebroadcast of the 11 o'clock news. One of my biggest pet peeves these days is blaring TV in public places. Why must you be entertained all the time? Several people in there appeared to be watching, so I dared not shut it off. I couldn't stand the noise, so I headed out of the hospital to stock up on Jolly Ranchers for Liz. It was kind of nice being out there in the middle of the night. The event was already so surreal; having empty corridors, closed stores, and general quiet magnified the strangeness of it all.

Liz came out of triage in a gown. Dr. Aron had told her to go home, but the thought of two more cab rides was abhorrent, so Liz insisted and they let her in. The only bad news: no room at the inn. We wandered the corridors, Liz padding along in her peds and weird double hospital gown (you know, the backless kind, but they give you two worn yin/yang style so it looks more like some weird smock thing), Patricia and I hovered, trying to make her comfortable. Liz's best position seemed to be on her knees on a pillow on the floor, with her head and shoulders on a chair. Several nurses walking by clucked at us for assuming this undignified position in the hallway, but hey, get us out of the manger and into the inn, and we'll stay out of your hallway.

After another hour or so, a room opened up, and we decamped to the scene of the crime. Patricia and I settled our stuff (extra pillows, bags, coats) into the closet, and we all started to pay attention to one of several previously unconsidered quantifiable variables which can take on such importance during moments such as this: dilation. Just how big was Liz's cervix? When we hit the hospital (about 2 am) it was four cm. You've got to get to ten before things really start to happen. It looked to be a long night, into a long day.

Liz had thrown up several times by this point, and had the diarrhea that comes in the beginning of labor. We’d been trying to get her to drink plenty of fluids to replace the ones she was losing, but it was a losing battle. By 4 am, Liz was feeling dehydrated and spent, and there was clearly still a long way to go. Patricia prescribed an IV to get some fluid into her, and the doctor concurred. The drip definitely helped Liz get rehydrated, but the tube meant she couldn’t walk around any more.

It was also the beginning of a progression we’d been warned about in our Bradley Natural Birth class. Once you have a vein open in your arm, it’s just that much easier to administer Pitocin (a hormone used to induce labor or speed it along), or drugs to ease the pain. These events tend to lead easily from one to the next, which is one reason the Bradley types (and our doctors too, it must be said) try to keep you home from the hospital as long as possible. It’s great to be in a hospital among experts should something go medically wrong, but at the same time, there is more of an emphasis on medicine and technology even when everything’s going smoothly.

Liz was still fairly miserable and weak, and the pain was really beginning to get to her. She hadn’t slept in nearly twenty four hours at this point, and the fatigue more than anything else led her to ask for the epidural, or “happy dural” as the nurses were calling it.

They brought in a special doctor to do the epidural itself. Patricia and I were asked to leave. We’re not sure if it was because the huge needle they use freaks out husbands, or if it’s a liability issue. Whatever, when we returned, Liz was indeed a much happier camper. The epidural is a local anesthetic, so she wasn’t THAT much of a happier camper, but the most intense pain had gone away. In its place was an extreme itch everywhere on her whole body. You see what I mean by the medical escalation. She was then given Benadryl for the itching. Benadryl (the allergy medication) relieved the itching, but made her sleepy and when she was awake, dopey. This turned out to upset her almost as much as the pain, as she had wanted this experience to be as clear and lucid as possible. But anything was better than the searing pain, and then that damn itching!

Continuing down the slippery medical slope, since she had already been given the pain killers, and was still “failing to progress” Dr. Aron suggested giving her the Pitocin to speed things along. Liz readily agreed. So much for natural childbirth.

By this point, it was morning. Both the doctor and the nurse changed shifts. Nurse Karen took over, and Doctor Susan Rothenberg came on duty. Our practice has three doctors, all of whom we had seen during the pregnancy and gotten to know during the pregnancy. We were pretty much equally inclined to deliver with any of the three, though perhaps the least favorite was Dr. Rothenberg. She had been there at the amnio, when I fainted, and I think may have I associated her with that, but that’s another story. As it turned out though, she was great.

Liz felt good enough to try to catch little naps between contractions at this point, and was still only six cm dilated. Dr. Rothenberg told Patricia and me nothing big would happen till at least after noon, so we should maybe take the chance to get some food , rest, whatever we needed. Patricia offered to go walk The Fur, and I went out to grab a bite of breakfast.

I strolled down to Veselka and got an egg sandwich. I ate it as I sauntered my way back up to Beth Israel. Things were less surreal with the coming of daylight, but I still felt pretty weird, what with the lack of sleep, intense emotions etc. I returned to the room feeling relaxed and rejuvenated by my walk and refuel.

Thus you can imagine my horror when I found Liz up on her knees, totally freaked out, several new wires sticking out of her, an oxygen line running in her nose, bustling activity all around her, and another nurse and doctor I’d not seen before engaged in a lot of hushed, cryptic conversations about emergency surgery, c-sections and the like.

The wires emerging from Liz were implanted directly in the Soon-to-be Sophia’s head, and were connected to a fetal monitor, which was turned up loud so her little heartbeat was echoing like a frantic drum . Turned out the last routine test with the external fetal monitor had shown a slowdown of the fetus’s heartbeat. The internal monitor was more accurate, thus all the new people in the room, and we too, you better believe, were focused on that little heartbeat racing out loud on the speaker. The decels, as they were called, seemed to be taking place during contractions. All the medical personnel huddled around the little tape crawling out of the monitor. Dr. Rothenberg hastily conferred with the nurses over the availability of the operating room, and instructed that the woman next door being prepped for it would have to wait. They nicked a little piece of skin off the proto-Sophia’s head so they could test her blood and see if she was getting enough oxygen. This sample was whisked out of the room, and shortly the out-of-breath technician literally ran back into the room announcing that it was in fact, OK.

Since mother and daughter both seemed to be doing alright at this point, the emergency C-section was put off, and we all continued to monitor the monitor. The doctor and nurse were listening for other things I’m sure, but I just about hit the ceiling every time the probe shifted and the heartbeat appeared to stop. My eyes would dart to the beats per minute reading: anything below 120 or so was considered a concern, and below 100 was definite trouble.

Thus began a long intense period of listening to this booming little chirp of a heartbeat, and staring longingly at the trace of paper the monitor kept spitting out. I gave Patricia a few more hours to sleep, and then called and asked her to come back over. Liz and I both tried to nap whenever possible, but it was hard with the constant beating of the heart, and the flurry of activity. Every couple hours Dr. Rothenberg would do an internal exam and pronounce the latest dilation: six cm, seven cm, eight cm, finally inching up to nine cm.

At one point, we heard a woman in an adjoining room yelling at the top of her lungs. Dr. Rothenberg looked at the nurse and they both rolled their eyes. “She’s wasting all her energy on that yelling, when she should be pushing...”

Finally, about 2 o’clock, it seemed that things were beginning to come to a climax. The decels had continued, but just on the borderline of being something to worry about. One of the main things Liz had desired when we were planning our birth was an upright position. A Caesarean section would be medically indicated, but if she delivered vaginally, she wanted to do it squatting if at all possible. The epidural had made her legs numb and there was no way she was going to squat. Nonetheless, determined as she was, Patricia, the doctor, nurse, and I all got together and contrived to flip Liz over and wedge her legs into the crease formed by the upturned head of the bed. We raised the head of the bed to near vertical, and Liz could hang her head and shoulders over the top. I stood there, behind the head of the bed, and linked arms with her and supported her while stroking her hair, and telling her how well she was doing.

By now the serious pushing had commenced. Dr. Rothenberg calmly told Liz to shut up whenever she yelled, exhorting her to put the energy into the pushing and not waste it on yelling. Dr. R. was a bit of a drill sergeant, which I think may have been one of the reasons we ranked her #3. But when it came down to it, I found her seriousness and professional manner very reassuring. One thing that bugged me about the other two doctors was the way they’d demur and say, “aw shucks call me Audrey” when I tried to call them Doctor. Dr. R understood the need for gravitas in an authority figure, and let us call her Doctor. She was certainly personable enough, and happy to chat during the long pauses between contractions, but her no-nonsense manner helped in the crucial moments.

Nurse Karen began a flurry of activity getting everything ready, unwrapping sterile packets, laying out arrays of tools, setting everything out just so. Dr. R started suiting up in a whole space suit worth of gowns, gloves, masks and whatnot. I linked arms with Liz, Patricia got around behind where she could see. I saw the nurse mouth to the doctor, “You going to let her do it in this position?” and the doctor answered with a sort of “Why not?” sort of shrug.

Right about now the head started to crown, and the moment was nigh. Neither Liz nor I could see thing one, so Patricia started doing play by play. “Here comes the head, I see her head!”. Liz was wailing in pain, despite Dr. R’s entreaties: “Two more pushes! Come on now, push and get this over with.”

Push she did, and again. Patricia:”Oh, she’s beautiful, her eyes are open! She’s coming out with her eyes open!”

Doctor Rothenberg glanced at the nurse and said, “Look at the cord, so that’s what the decels were all about.” Turns out little Sophia had her umbilical wrapped around her neck not once, not twice, but thrice. Whenever Liz’s uterus contracted it was squeezing her little neck and cutting off her blood. All the worry about decels, staring at the squiggles on the chart, and listening to that eerie audio track turned out to be OK. Dr. R gently untwisted the cord from around her neck.

With the head out, Liz could feel the end, and roused one more push. Then the shoulders, and then whoosh, out she came! Liz’s and my first sight of our daughter was a pair of tiny perfect feet, lying in a pool of blood and guts and God-knows-what framed between her mom’s legs. Just two tiny perfect feet.

I happened to catch sight of Dr. R’s face, and for just one moment I saw her professional demeanor crack, a huge smile lit her face, and my heart leapt because I knew it was alright.

I couldn’t stand it anymore, so I made sure Liz was ok, and disentangled myself to go around and take a look.

There she was, a little worm, not breathing yet, but that was alright because she was still connected to the cord. The classic spank to make them yell is now an urban myth. Dr. R invited me over to cut the cord. I did, and Sophia uttered her first cry, a teeny little “La” that made you want to laugh more than cry. Lying in a huge puddle of bodily fluids the likes of which I’ve never even imagined.

She was placed on Liz’s chest for bonding, and we all marvelled at the beautiful new life.

Next, the nurse scooped her up into the drying thingie which looks pretty much exactly like the device they warm French fries in, you know, the clear plastic tray with a lamp over the top? I went back around the bed to check on Liz, who was expelling the afterbirth. Dr. R examined it, and shared her findings with Patricia, who of course lives for those moments. Liz had only torn a little and so received three stitches.

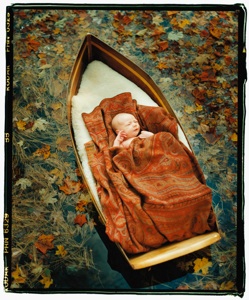

Meanwhile, Nurse Karen had been giving Young Sophia the Apgar tests. She scored 9.9, her little blue hands keeping her from a perfect ten. Karen then wrapped her in a swaddle and handed her to me. The swaddle was so tight it was like holding a bowling pin, nothing creature-like about it. I gazed at her wise little face in wonder, and then had the presence of mind to dig out the digital camera and shoot off the shots you’ve probably seen on the web by now. The soft light coming through the window, the digital cheesiness, and their combined bewilderment made both of my ladies glow like a couple of newly earthbound angels. Which is I suppose, just about exactly what they are.

all material ©copyright chris carroll 2012